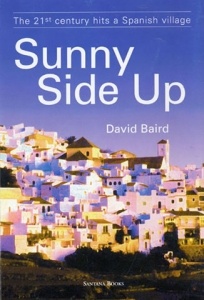

Sunny Side Up |

|

sunny side up

Author: David Baird

ISBN: 978-84-89954-36-6

Publisher: Santana Books

When my neighbour Caridad crashed through the front door, crying "What an opportunity! There's a bus trip to Córdoba. You can't miss a chance like this", I had no difficulty turning it down.

This was no time to go gallivanting around the country, I explained. Córdoba was out of the question. The last thing I needed was a village outing...

The bus left at 4am. Everybody was on it - except Caridad. The minutes ticked by and Antonio revved the engine and peered down the darkened village street, muttering into his stubbly jowls. Finally, shortly before 5am, Caridad hove into view, bucketing down the street in a whirlwind of flustered gesticulations, flying hats, skirts and baskets, trailed by what looked like a flock of scurrying chickens but proved to be her innumerable children.

We rumbled off, swinging around hairpin bends, frightening owls and sleeping pigeons, lurching past cortijos where mules blinked at us in surprise, down to the coast road. Caridad kept up a lightning dialogue with Bruno the butcher, each shouting at the tops of their voices since they were at opposite ends of the bus. Their obscene allusions and subtle quips kept everybody in convulsions. Or, more correctly, it kept Caridad and Bruno in convulsions. The rest of us tried to get some sleep before dawn broke.

After an hour or so, a 10-minute halt was made for coffee, anis, cognac, sol y sombras, sticky pastries, potato crisps, sunflower seeds and peanuts. An hour later - after an emergency in the cafeteria toilets involving Caridad's children - we were on the road again. The radio was turned up full blast to make everybody feel at home and to give Caridad's voice some competition.

As Antonio stepped on the gas, the faces of several passengers underwent alarming changes. The cry went up for "Air! Air!" and windows were hastily flung open before the coffee, anis, cognac, lemonade, sticky pastries, potato crisps, sunflower seeds and peanuts made an unwelcome second appearance.

On the outskirts of Córdoba, Caridad leaned across to the driver and, fluttering her eyelids, said: "Listen, can you drop me off before you get to the centre so I can visit my family? It will only take a minute."

Obligingly, Antonio pulled off the main road and entered a side street. Caridad took control: "Straight ahead. Right at the top of the hill, then left at the traffic lights. Now left, then left again. Down that side-street."

Her fellow-passengers looked at each other with a bemused air as we plunged ever deeper into a maze of back-streets. Finally, the bus stopped before a small house and Caridad descended. We waited, and waited. Then Caridad returned and called to everybody to come and meet her relatives. She darted quickly away before anybody could nail her to her seat. People from the neighbourhood began to gather and gossip. Caridad's children started playing games with the local kids. As the minutes ticked by, Antonio the driver looked at his watch and muttered away.

Caridad popped her head briefly out of a house down the street to say her father had gone for his morning stroll but would be back soon. We waited, but he failed to return. At length, Caridad had to be forcibly reloaded with her children. The bus set off. But a hundred yards down the street she uttered a shriek.

"There he is! There he is!"

Out leaped Caridad to embrace her father. Her children and half the bus followed. Antonio sighed. One or two unsociable types mumbled something about hoping to see the Mosque before sundown.

"Vamonos! Vamonos!" cried my fellow-trippers, starting to lose their patience.

At length, when it looked as though the pueblo outing was about to dissolve into a protest demonstration and visions of sirens wailing and visored riot cops began to swim through the imagination, the family reunion broke up. Caridad and her father were bundled on to the bus and we arrived at last in the centre of Córdoba.

A new difficulty then arose. Since Antonio was working to what may be kindly described as a flexible schedule, we had to stick together. And worse still, due to unforeseen circumstances - Caridad did not bat an eyelid - only half an hour could be allowed to visit the Grand Mosque.

Thirty minutes to appreciate the grandeur of one of the Moors' finest pieces of architecture, 30 minutes to admire this wondrous creation of the caliphs, 30 minutes to examine those 850 columns of jasper and marble, to study the delicate mosaics, to gaze in awe at friezes and cupolas and galleries and Arabesques. We did it.

We raced up and down the vast echoing naves. We flashed past chapels and arches, throwing brief, all-embracing glances at the wonders of the past. We scorched past slow-moving groups from Idaho and Munchen-Gladbach, trampled down stray old ladies studying their guidebooks without due care and attention, and with a final burst of speed burst once more into the open.

It was a magnificent operation, carried through with split-second timing. Flushed with triumph, we managed a second-wind sprint to the bus. There was nobody there. Not Antonio. Not Bruno. Not Caridad. Nor anybody else. Just three or four of us, the front-runners. After waiting half an hour during which a few stragglers turned up we decided to drift off and take a look at the bullfight museum. That proved a mistake because in our absence the other half of the party turned up and decided they might as well go and look at the Roman bridge.

By the time everybody had been rounded up, it was lunch-time. That put the party in good humour, ready for the visit to the zoo. The wildest thing that most of the pueblo had seen before was Pepe El Panadero dancing on the Casino bar-top at 3 a.m. during the last fiesta. Thus the sight of so many bizarre creatures of the wild was an instant source of shock and delight. The zoo was a hit, the hit of the whole outing.

The hippopotamus pen drew cries of amazement as its occupants cooled themselves in a pool and yawned in expansive hippo style. Gazing into the abysses thus exposed, Bruno chuckled: "Ay que ve! And we thought you had a mouth, Caridad. Look at that one!"

"It looks just like Manolo de los Cuatro Vientos," said another.

"No, it's got more teeth than Manolo."

Next stop was the monkey house and no sooner did the party catch sight of the chattering, red-bummed animals than they fell about laughing.

"Imagine having to share your bed with one of those Butano-coloured backsides," said Bruno.

"Never mind the backside. What about the front?" cried Caridad, provoking loud guffaws. Except from one or two señoras who eyed Caridad with profound disapproval.

Suddenly there was a disruption. One of the children came running up, his eyes almost popping out of his head, crying: "Over here, over here! You've never seen anything like it."

Everybody rushed over to a nearby compound. Their astonishment was unbounded, limitless. They hardly knew whether to laugh or cry. It was just too much.

"Cojones! How long do you reckon it is, Paco?"

"Fifty centimetres, I'd say."

"Nah, it's close to a metre, at least."

"We could do with one of them in the pueblo," said Caridad.

"You wouldn't get any more complaints from the women."

They kept up the wisecracks for half an hour as they surveyed a zebra on heat and tried to estimate his impressive vital statistics. It was generally agreed that now they had seen it all. None of Cordoba's other diversions were likely to match this.

We had done the city. It was time to go. We climbed back in the bus and headed out of Córdoba. But first we had to drop off Caridad's father. Once again we halted while the old man embraced all the children and kissed Caridad and a few other relatives entered into the spirit of the occasion. A clamour arose from the bus as the ceremony dragged on. Enraged by our lack of compassion, Caridad stormed aboard, eyes flashing, tears streaming down her cheeks.

"Can't I even say goodbye to my own father? Don't you have any feeling? How would you like it if it was your father? I see him only once a year. My own father!"

The children began to cry and the old man standing at the curb put a handkerchief to his eyes. Then the other women on the bus also began to weep. Because it was true. They couldn't stand Caridad. But after all it was her father and they had fathers too and it was hard having to say goodbye to your own flesh and blood. Bathed in tears, we lurched out of Córdoba.

We swept across the plain and up mountain passes and Pepe led the singing and the handclapping and somebody passed around a bottle of brandy. Only on the last stretch up to the pueblo did the bus fall silent.

It was well after midnight when we rolled to a halt and everybody tumbled out, drained by the rich experiences of the day. Giant hippos and over-endowed zebras haunted the pueblo that night and for quite a while afterwards. The Córdoba outing was a fantastic success. That's what Caridad tells me anyhow.

This is an extract from David Baird's book Sunny Side Up - the 21st century hits a Spanish village.

Buy your copy of Sunny Side Up by David Baird

When my neighbour Caridad crashed through the front door, crying "What an opportunity! There's a bus trip to Córdoba. You can't miss a chance like this", I had no difficulty turning it down. This was no time to go gallivanting around the country, I explained. Córdoba was out of the question. The last thing I needed was a village outing..

Buy from Amazon.co.uk or Amazon.es

Sunny Side Up by David Baird

Sunny Side Up by David Baird